It’s fab time! The following story takes place in the last week of February to the first week of March – yep, that’s just over 3 weeks, reaching into 2 weeks, until the bot had to be in the crate! In fact, a lot of the earlier photos here were concurrent with finishing out the drivetrain changes and electronics module, since the mechanical modifications were first priority.

Alright, the first thing to do after two years of stagnation and one entire shop move is to take inventory. Some of Overhaul’s parts had wandered off into other projects or been repurposed, and others had been sold to needy builders elsewhere. Oh, and some things instead were to be deprecated and thrown out.

I was first out to ascertain how many good drive motors I had remaining. I originally built a whole bunch of spares and only ended up using two or three. But the lift motors at the time were low on stock at Hobbyking, so I only had four lift motors total – one of which was burnt out and the other had a severely damaged gearbox from (likely) the rumble and post-season shenanigans.

There were also other parts being counted – sprockets and drive hubs, and hardware relevant to the liftgear which I only had a few of to begin with.

By the end of the day, I had a good idea of what needed to be ordered from McMaster the following Monday, as well as what parts to ask HobbyKing for!

I began the stripping down of the bot during this process. Poor Overhaul – it’s mostly been living on a lift cart behind my work area, usually causing me to run into it in some way on a regular basis, causing a pattern of injuries on my leg which would have been highly suspicious during high school.

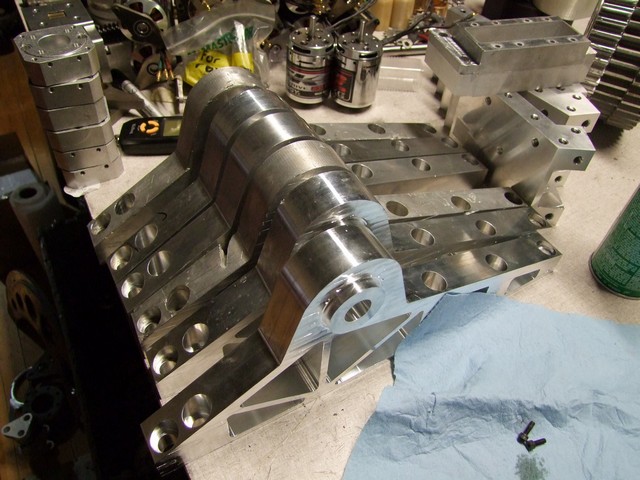

Breaking the bot down was important since I would want to start over with all new fasteners and ascertain the status of all of the parts, such as where a frame rail might need to get cleaned up or if this or that drive hub was about to let go anyway. There were also quite a few parts which were going to receive lightening in my efforts to make weight for DETHPLOW. Basically everything above in blue is being replaced completely, and a lot of parts which went into the now-previous design head will have to be deprecated.

Ah, the sad electrical box. Overhaul hasn’t been operational since a year and a half ago when I sold the DLUX 250 reflashed ESCs to Ellis for Robot Wars. To my surprise, this damn thing still powered on. There is a single brushed RageBridge inside to run the former clamp motor, an A23-150 sized Ampflow motor, as well as a BEC module.

Oh well – everything which caught fire is considered automatically sketchy in my book, and this box had an entire unassembled spare if I somehow needed another one – so I salvaged the bus bars and some intact wiring harness parts and unceremoniously chucked the rest.

Overhaul is probably my current masterpiece in terms of design-for-assembly and design-for-service. I put more thought into how things go in and out into this bot than probably every other project I’ve ever made, combined. It’s actually very easy to knock down as one person, since the majority of the bot is supposed to be serviceable by 2 people in under 5 minutes. It takes on average only 2 minutes to release a set of drive motors and under 60 seconds to separate the upper and lower halves of the bot at the arm towers, after which the set of lift motors comes out with only 4 bolts.

The revisions will see some of this go away – for instance, the frame rail brace plate would add a dozen bolts and a different tool to the process. However, I was fine with this – at BattleBots with the current format, you usually have several hours of notice before fighting, if not days. It gets tighter around the playoffs and finals obviously, but the quickest turnaround I’ve witnessed was still on the order of 2-3 hours. If I was scrambling to replace frame rails that hard, it means I’m doing pretty damn well.

On the plus side, the actuator and upper clamp retainment strategies have been changed to be more easy to service.

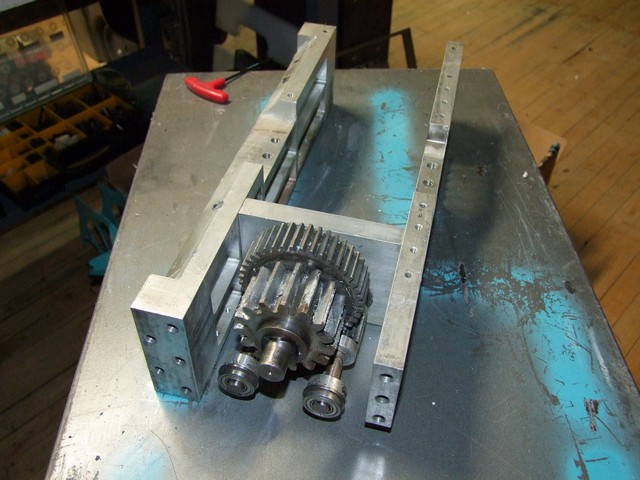

Well, when you get down to the basics, Overhaul is just a series of gears.

All said and done – this is what my table and bench area looks like. I sorted the remaining spare frame rails by type, since each type needed a different kind of surgery or modification.

Chibikart makes a cameo in this photo.

There was about 8 pounds to lose in the frame, spread across a few parts. Overhaul weighed in at 247.0 on the event scale during Season 2, so I used that as a cross-reference to the CAD weight of 240 pounds. To make sure DETHPLOW took me up to the same physical end weight in replacing the separate heavy wedges, and also taking into account the new frame brace plates, I had to get the bot down to around 230 pounds. The rest of the ‘missing weight’ was to be made up in the battery and ESC assembly being smaller and lighter.

Above, I use an annular cutter (also some times called trepanning cutters) to empty out some of the interior of the Epic Lift Gear. If you’ve never used these before, they’re like specialized high-precision hole saws for metal, and can cut a large hole very cleanly and quickly. They used to be very expensive and specialized, but you can find Chinesium sets now that work fine for under $100. This one was driven in low-gear on Bridget.

The arm towers themselves also lose a bit of meat, with each side getting 1/4″ removed. In a mild perversion of their use, I actually used the same 2″ diameter annular cutter to make the circular boss by simply leaving the interior portion and machining the rest away.

It was now the first week of March, and life suddenly got much more exciting.

I had been scouring the country for a more consistent source of the 4mm AR400 steel that makes up Overhaul’s clamp and fork profiles. Basically, the material seems to come and go at McMaster, who also seems to source it from the depths of a tropical rainforest as all of the AR grade steel I’ve ever gotten from them has been covered in rust and not a single one has really been straight.

Through a lot of calling around local steel companies, I was given an inside sales contact at SSAB – the international manufacturer of the UK/Europe robot fighting circle’s preferred armor steel, Hardox. The gist of the conversation was essentially “Hold on, what did you say you guys were building? Let me talk to the sales manager and we will see what we can do”.

Only afterwards did I do some research and found that SSAB was essentially the U.S. Steel of Sweden. To be fair, I’m not sure what I was expecting, since it’s not like some small mom-and-pop operation produces 8 million tons of high strength steel alloys a year.

So there we go – I’d like to formally welcome SSAB Americas as a sponsor of Overhaul this season! This explains the big Hardox logo on the Equals Zero Robotics Facebook page now.

They not only straight up sent me a diced up 4′ x 8′ plate of 4mm Hardox 450, but also helped find a local steel distributor who had a fast-turnaround plasma cutting service for even more Hardox. This will come into play just a little later.

Alright, presented with several hundred pounds of steel, I will obviously go waterjet. I paid some hush money to the MIT Edgerton Center and popped out a few parts on the Omax 5555 in an evening. I started with 2 full “heads” for Overhaul and basically all of the kibbles which go into the new lift hub design, as well as one set of titanium brace plates.

Here’s the finished parts in the middle of some post-machining.

Back at my shop, I cleaned up the actuator-mounting bore on the clamp side plates. The actuator trunions will ride directly in these holes, so I wanted a not-sandpaper finish here. I didn’t have a carbide boring bar that fit my old boring head, so I reground the old HSS lathe rool I used in there and just ran it very slowly and gently to scrape the little bit of Hardox off.

Harder steels might be horrifying to machine, but they do leave wonderful finishes if you know their weaknesses.

I made a design change to the lift clutch which entailed cutting out some new parts. I wanted to increase the clamping pressure significantly because Overhaul had a lot of trouble actually hauling stuff over during Season 2. To do this, I made new thicker pressure plates such that the tightening nut could exert a lot more force without causing bowing and decreasing of the contact area. I also switched to a higher-friction clutch material (what McMaster calls their high-coefficient of friction), from a medium one.

Additionally, I made over a half pound back here by machining down the Epic Lift Pinion and clutch gear! Technically, that shaft also never ever had to be made of steel – 7075 aluminum would have been highly reasonabel… but I already had slugs of steel sitting around in the right size back then…

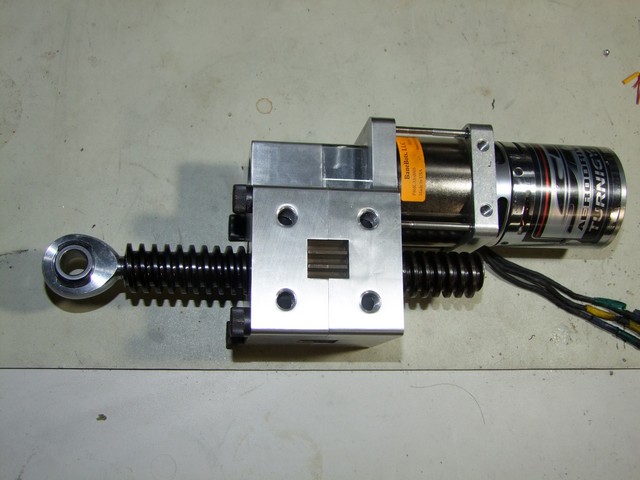

Just a couple of days later, the new actuator bodies arrived from my Chinese CM.

Oh. My. Baby robot Jesus.

Probably the most gorgeous assemblies I myself have ever designed and carried to fruition (if I do say so myself). The story of the gear-nut is a tragedy upon itself. I originally threw it at my Chinese shop along with the billet halves, expecting them to basically tell me to quit it with my English Acme thread in the middle of a gear nonsense. I was fully expecting to just buy two bronze nuts and shove machined stock catalog gears around them.

The problem is then they asked me for a sample of the 1″-4 leadscrew, which is obviously not easy to get in China, as an assembly fitment. They already made one. What?

Absent the ability to mail a chunk of leadscrew (which I didn’t even order yet) in a timely fashion, we settled on the next best thing: I would send them a 3D model of the leadscrew, and they will SLA resin print it and use it as a fitment test. These gearnuts have less slop in the Acme thread than my Bridgeport does.

In the end, it was worth it! The gearnuts are probably the highlight of this whole operation – on almost every project and bot, I have something I call the “penising piece”, referencing the unfortunate tendency for us guys to put a lot of effort into something very showy and impractical for the sake of one-upping each other.

You know what I’m talking about. Don’t deny it. Think about what sport this is.

Too many parts and assemblies like that and your whole project becomes very out-of-scope quickly. Trust me on this, I used to do entire projects that way.

That is not industry terminology. Do not dare try to make it standardized.

There was only one “quality control” problem, and it wasn’t the Chinese’s fault. You see, the thrust bearings I specified on McMaster had a nominal outer diameter, which I designed the pocket for. It in fact was a full 0.02″ larger in real life.

I’m technically not even mad – it’s a thrust bearing. What kind of dumbass tries to make a radially tight-tolerenced fit on something like that?!

The outer shell of those bearings is just a stamped piece of steel – it doesn’t acually Bearing anything, it just vaguely holds the upper and lower races together so you don’t sprinkle the rollers everywhere.

Sadly, I had to bore out my beautiful Chinesium to accommodate the ingrates.

Here is how things fit together. The big thrust bearings sit directly on the face of the gear. The pinion shaft is retained via snap ring and has another bearing that carries it, located in the half not shown here.

And this is how it fits together. I’m quite thrilled with this unit! It ended up weighing about 1lb less than the fiasco I designed last time around, is much smaller and also capable of much heavier loads due to the large trunnion diameter and thicker leadscrew. The rod end is threaded into the leadscrew and retained with two cross-drilled 1/8″ roll pins each.

Next time on Overhaulin‘ – lots of welding. so much welding.